A great deal can be said about a society by its artwork. Through some works of art secrets can be revealed, misjudgements corrected, hidden corners examined. A painting by a Victorian artist named Richard Dadd is currently up for sale, and is just such an art work.

However what it reveals is the strange reality of the mentally ill in Victorian times, as well as the curious twists and turns creativity can take, both then and now. Most of all, it shows that we are really not so different from our Victorian ancestors.

The following is reposted from More Intelligent Life.

Blood on the Tracks

The most violent work of a deranged Victorian painter comes to auction at Bonhams in April. Fiametta Rocco, Books and Arts editor of The Economist, sees pathos in the details …

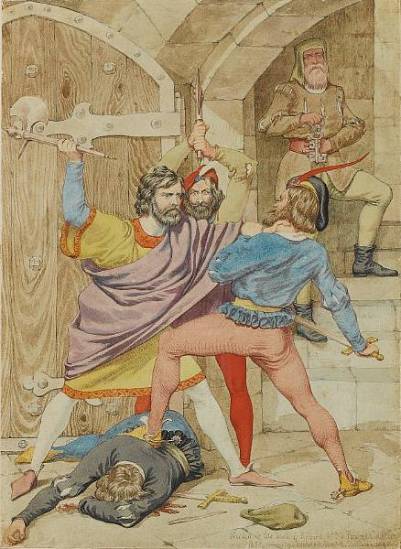

“The Death of Richard II” by Richard Dadd

In 1974 Patricia Allderidge, a British museum curator, wrote the first biography of the great Victorian painter Richard Dadd, who had died nearly a century before.

In two short paragraphs on the first page she explains why Dadd was such a unique and exceptional figure. He began working the year Queen Victoria came to the throne and John Constable died. By the time of his own death, the pre-Raphaelites had come and gone and the first French Impressionist exhibition had taken place. The intervening five decades had seen the English picture-viewing public overwhelmed by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, blandished by dogs and children and charmed by an unending flow of bandbox beauties. In chronological terms, Dadd was thus the complete Victorian.

But Dadd himself was utterly untouched by this. At the age of 27 he was cut off from all society-even the influence of friends-by what Ms Allderidge describes as “the most effective barrier this side of the grave, the walls of a criminal lunatic asylum.”

Bonhams In need of psychoanalysis

In 1843, having become increasingly violent and delusional, Dadd stabbed his father and cut his throat while the two were out one summer’s evening on a country walk. Dadd fled to France, where he intended to kill other people he believed were possessed by the devil, but was instead arrested and certified insane. From then until 1886 he continued what he had first set out to do in life: painting and drawing. First in France, then Bethlem Hospital in south-east London and later at the newly opened Broadmoor asylum in Berkshire, he worked to please no-one but himself, knowing, Ms Allderidge says, that his pictures “could never in his lifetime alter his personal status by a hair’s breadth.”

No other painter stands alone as such an isolated phenomenon. Unencumbered by the need to earn a living, enjoy a social life or raise a family, Dadd had the freedom to push his creativity along paths that could only be trodden alone. The incarcerated artist worked, as Ms Allderidge says, “almost outside time itself.”

Educated to know his Shakespeare and his Bible, Dadd peopled his paintings with literary and biblical figures as well as an enormous range of fairies and fairy animals drawn from myths and legend. “The Death of Richard II” (pictured), which comes up for sale early next month, is the most violent picture in Dadd’s oeuvre, and is particularly interesting because of his background.

It is taken from the final act of the Shakespeare play, when King Richard is attacked by Sir Pierce Exton, a courtier, and his servants at Pontefract Castle. Richard has already killed one servant, whose body fills the lower left-hand corner of the picture (the red pooling under the body seems to have been the only time Dadd actually painted blood). In this scene, Sir Pierce has raised his axe and is about to deal the final, regicidal blow.

Painted in soft, muted colours, the picture shows Dadd’s customary care with detail, with every grain of wood and every hair carefully drawn in. What comes across most strongly, though, is the power of the picture and its deep psychic connections. The staircase where the action takes place has a crowded, enclosed feel, which was probably not dissimilar from the mood of the high walls and heavily barred windows that formed Dadd’s daily landscape in the asylum. The figures have a frozen, static look that makes the imminent killing that much more chilling.

The central figure, with his look of intent and his bulging eyes, is one that Dadd painted again and again. He can be spotted in an earlier scene taken from Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” and would reappear in virtually every one of the “Sketches to Illustrate the Passions” that Dadd worked on between 1853 (the year after he completed “The Death of Richard II”) and 1855. With his beard and his floppy, page-boy haircut, the assailant looks remarkably similar to the image of Dadd sitting at his easel in the only photograph that survives of him.

Some of the “Passion” series were kept by the reforming physician-superintendent at Bethlem, Sir Charles Hood, but many of Dadd’s pictures have been lost. This may be one of the reasons why his work rarely comes up for sale. Since 1990, only 11 oil paintings and 20 watercolours have appeared at auction. Some have sold well, some not at all. Andrew Lloyd Webber surprised many in 1992 when he paid £1.5m ($3m) for Dadd’s magnificent oval fairy painting, “Contradiction: Oberon and Titania”. Last December two previously unknown watercolours, painted in Jerusalem during Dadd’s first journey abroad, estimated to sell at £3,000-5,000. One eventually sold for £11,000 and the second for £29,000.

When it last came up for sale, in November 1990, “The Death of Richard II” sold for just under £8,000. At £15,000-20,000, its current estimate looks like a bargain.

2 Comments

Comments RSS TrackBack Identifier URI

I find myself coming back and looking at this piece over and over… It’s compelling to me in some way I don’t quite understand, my mind looking to make sense of each and every detail. And each time I keep catching and focusing on the man in the background. He’s so very creepy to me, just standing there, watching, not seeming to be touched by the scene.

While usually focusing on the more lurid details, over the actual histories of events, the Popsubculture.com ( http://www.popsubculture.com/pop/bio_project/richard_dadd.html ) article is actually fairly well-done, and mentions more on Dadd’s influence, then and now, and on his paintings.

I find it even more interesting a mention of another work of his, Fairy Feller’s Master Stroke ( http://www.popsubculture.com/pop/bio_project/images/dadd2.jpg ) which, even now, cannot properly be appreciated without “raking light” to highlight the build-up of paints he laid to canvas over the course of nine years’ work.

Obsessive? Obviously. Driven? Yes. Insane? Undoubtedly.

Gifted? Also true. Madness and artistry, like madness and genius, go so very often hand in hand.